Make Your Experiences Count. They Can Change the World.

LET’S BRING ALL OF OUR KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCES TOGETHER.

TOGETHER WE KNOW MORE. TOGETHER WE ACHIEVE MORE. TOGETHER WE DO BETTER.

LET’S BRING ALL OF OUR KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCES TOGETHER.

TOGETHER WE KNOW MORE. TOGETHER WE ACHIEVE MORE. TOGETHER WE DO BETTER.

Published: April 13, 2021

Gloria Alzate Castaño is the director of our partner organisation Conciudadanía in Antioquia, Colombia. The organisation was founded in 1991 and since then has aimed to “develop pedagogical and mobilisation actions in the Department of Antioquia, in order to secure the people’s rights”. They pursue this objective through the promotion of “peaceful coexistence, peace building, development planning and the strengthening of local democracy through the exercise of full citizenship for men and women, within the framework of a social state governed by the rule of law”.

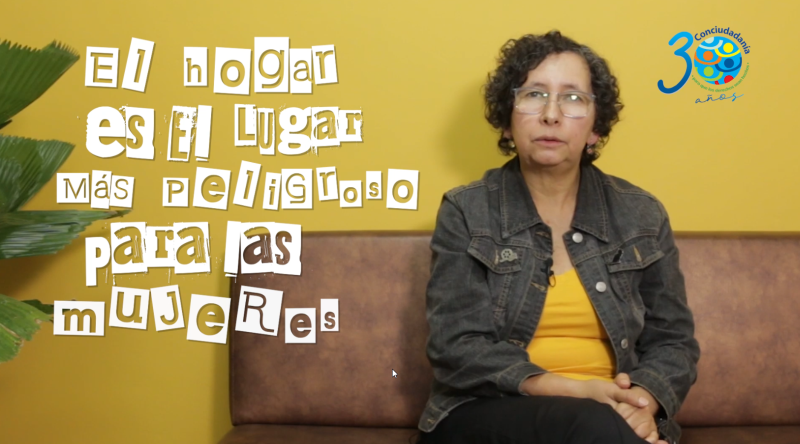

In this text Gloria Alzate summarises the situation and the difficulties that women are facing in terms of COVID-19 and virtuality. She also shares a video (in Spanish) that was made to highlight what is needed to achieve more equity and equality between women and men.

For some people and sectors of society, the pandemic and its resulting confinement has meant opportunities; but for others it has meant poverty and paralysis. In a positive way, it has brought us back to our centre, to our home, to our family; we were on the run all the time, interacting with many people every day, always busy with the results of our work, relationships, political discussions, socio-economic indicators.

Then, virtuality became the lifeline to keep us connected to the outside world, while work crept into our home, which has become our office. Circumstances that at first glance result in favourable conditions for many people, but which, observed in detail, have not been favourable for everyone, especially not for women.

Although several companies or businesses adapted to the needs, managing to maintain or even increase their profits, as teleworking meant a reduction in fixed costs, higher productivity and therefore higher income; and for some workers it meant savings in money and commuting time, no more cold, reheated or restaurant meals; for a large part of the population, these new conditions that came with the pandemic meant unemployment[1], a reduction in working hours or sales and therefore in income; poverty, hunger and anxiety about the next day.

[1] In January 22.7% of women and 13.4% of men were unemployed, according to data from the DANE director presented in the Caracol news programme on 26 February 2021.

And if inequity and social inequality in general had already been a problem in Colombia, the COVID-19 pandemic turned it into an undeniable mayor issue – especially so in terms of gender inequality. Old and new elements came together and shaped the reality of women in a very harsh way. Gender gaps – which refer to the comparison between the opportunities of men and women – became more evident, as well as domestic violence and the double (or triple) burden resulting from the combination of wage labour and care giving work.

Women have had to make difficult decisions to the disadvantage of their independence, income and personal fulfilment during the pandemic; for instance have been to reducing their working hours, opting for independent work in order to have flexible working hours and to be able to reconcile the two jobs: paid work and “housework”. Others have found it necessary to quit their jobs, because when it comes to deciding as a couple who will quit in order to have more time to care for their children, “normally” it is the woman who does so[2]. According to the Yo No Renuncio Association, which conducted a survey with 7,500 valid responses from women with and without children between 12 and 14 February 2021, “22% of women have given up their job or part of it to take care of their children and 37% have been denied teleworking even though technically it would have been possible”. Also, the findings highlight “that when the child has to stay at home in quarantine, in 8 out of 10 cases it is the woman who takes care of the child”[3].

[2] According to the Vice-Presidency of the Republic, "65% of the employed population of women in Colombia is working in the commerce and services sector, the one most affected by the COVID-19 crisis, and around 6 million women are at risk of losing their jobs" Vice-Presidency of the Republic. Women in times of Covid-19, August 11, 2020. According to the director of DANE, in the news presented on Noticiero Caracol on 26 February 2021, in January, the unemployment rate for women was 22.7%, while for men it was 13.4%.

[3] Cristina Saldaña. Holidays, leave and unpaid days: this is how working mothers cope with their children's quarantine. El País, 16 de febrero 2021.

The overload of work generated by the coming together of paid work with (unpaid) care work in the same physical space (the home), plus all the members of the family demanding that women take care of them, explicitly or implicitly, has reinforced – what feminists have for so many years called – the sexual division of labour and the double or triple working day, which is nothing more than invisible work.

Multitasking, food preparation, household cleaning, family health situations, home schooling, emotional support, added to the eight hours of work – which are almost always more – are the factors that increase the demands on women because of their being a woman. That is how it is and always has been. Stress, permanent exhaustion, anxiety, in many cases health complications, and of course, the frustration of the feeling that this will always be the case are among women’s daily companions.

This reality is compounded by subtle situations in everyday life that reveal major differences in cultural behaviours that prioritise men’s work. In this respect, research on gender and unemployment being carried out by Aliya Hamid Rao, a sociologist at the London School of Economics, suggests that there is “a tendency to divide the spaces in the home, when both partners telework, as follows: quiet places, such as offices or separate bedrooms, are reserved for men and common areas such as the kitchen, dining room or living room for women”, or that “the home is not a neutral space: it is steeped in gendered expectations and the obligations that family members have towards each other”. The research even states that fathers were able to get space and time to devote to their tasks, while mothers had to improvise both time and space, as they were seen as caregivers and their role as workers was minimised, to the point that their option – in many cases – was to work in the early hours of the morning or in the evenings.

Some men and women will surely say that this has changed, that there are now men who take on household tasks without any complications, and this is indisputable. It is true that there are men who are committed to their role as fathers as well as providers; however, it is also true that historically “this distribution was already unequal”, as the women of the Association Yo No Renuncio say, and that it is essential to continue to carry out political actions to reduce this imbalance in order to achieve a society of equity.

In addition to labour inequality, there are determining conditions such as the gender digital divide, understood as the inferiority of women compared to men in terms of access to digital information, education and knowledge of ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies)”[4], which is particularly relevant in times when teleworking is the norm. One indicator of this gap is the percentage difference between women and men working in the technological development sectors, which according to a study carried out by Oxfam – Oxford Committee for Aid Against Hunger – “only 13% of the professional staff in these sectors are women”.

[4] Digital gender divide, what it is and how to overcome it. OXFAM

In this regard, what Conciudadanía’s team of advisors has been able to observe in relation to the women we work with, many of whom are dedicated to the care economy and the exercise of their community and social leadership, is the difficulty they have in accessing good telecommunications equipment, which is often prioritised at home to meet the needs of men’s work or for the virtual education of their children. This, added to other conditions such as low knowledge and use of ICTs, lack of economic resources to pay for internet service (which should be a right) and even their place of residence, as in many cases they live in rural areas with poor connectivity. Proof of this is that according to DANE, only around 26% of students in rural areas have connectivity compared to 89% in urban areas[5]. And if this is the case for students, imagine what the situation is like for rural women.

[5] Virtual education: fact or fiction in times of pandemic. Pesquisa Javeriana.

Faced with this situation, governments must advance in the massification of ICT use and access to connectivity, in compliance with Colombian Law 1341 of 2009, which establishes the criteria for the massification of ICT use and the closing of the digital divide: “The Ministry of Information Technologies and Communications has the task of reviewing, studying and implementing strategies for the massification of connectivity, seeking systems that allow reaching the most remote regions of the country and that motivate all citizens to make use of ICTs”. Article 38.

It is also necessary to implement programmes for the development of new competencies and digital skills in women, which will facilitate their labour insertion in a world globalised by virtuality and the use of new technologies. It is also important to regulate teleworking with a gender perspective that allows, for example, flexible working hours. It could be useful to overcome stereotypes that consider that men are more capable of performing in the world of ICTs and to make visible the role that women have played in high positions of responsibility.

In this reflection about the meaning of working from home and virtuality for women, it is impossible not to recall the disproportionate increase in violence against women during the pandemic. Bearing in mind that the highest percentage of perpetrators are family members and that before the pandemic, homes were already considered one of the most dangerous places for many women, especially at night or on weekends when their partners arrive; the truth is that with the confinement and permanence of men in the house (day and night demanding attention from women, not always in the best way), daily conflicts and therefore the risk of violence against women has increased and worsened.

The indicators show an increase in gender-based violence, which is exacerbated by the confinement and limited access for women to public services for care, prevention and punishment of violence, which are not considered essential. The data are compelling: between March 25 and December 31, 2020, there were 21,602 calls to the 155 line for domestic violence in Colombia, which accounts for an increase of 103% compared to the same period in 2019. 94% of these calls were made by women. The 123 line received 4,584 calls related to intimate partner violence, with an increase of 53.8% between March 25 and November 10, 2020, compared to the same period last year. Even more serious, according to data from the Attorney General’s Office, between January 1 and October 26, 2020, 143 victims of femicide were registered[6].

[6]. We can all put an end to violence against women. Minsalud, November 25, 2020.

In the words of the World Bank’s director for Colombia and Venezuela, Ulrich Zachau: “Women face particular vulnerabilities, such as worse working conditions and a greater burden of care, among others, which are exacerbated in times of crisis like the one we are experiencing. And if we add to this panorama the fact that nearly 40% of households in Colombia are headed by women”[7], the situation becomes even more complex.

[7] Vicepresidencia. July 2020. Humanitarian aid for mothers heading households amidst a pandemic crisis.

Although the Colombian cultural and social context has perpetuated the conditions of inequality between men and women, which have worsened with the increase in teleworking, paradoxically it is women who have to a large extent been the ones to shovel the current crisis, through community, social and political work, the scavenging in the informal economy and above all through their care work (in the home and in health centres), which puts them at the front line of risk.

Caring for life is a social and political issue. Social, because it concerns us all, and political, because it involves actors and decision-making spaces that favour fair development. That is why it is urgent to make the Law on the care economy effective, valuing and recognising its contribution, making gender roles more flexible and redistributing them, as well as state care programmes, in order to provide women and men with better conditions for a dignified life.

This article is a call to the women’s movement, women’s organisations, politicians, public and private institutions, and civil society organisations to activate their advocacy work and to take the necessary measures to reduce or mitigate the effects of these violent, social and working conditions that affect women’s rights and wellbeing.

We are all waiting for the vaccine and self-protection measures to enable us to overcome or minimise the risks of COVID-19 infection. However, it is also true that the digital era is here to stay and with it teleworking.