Make Your Experiences Count. They Can Change the World.

LET’S BRING ALL OF OUR KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCES TOGETHER.

TOGETHER WE KNOW MORE. TOGETHER WE ACHIEVE MORE. TOGETHER WE DO BETTER.

LET’S BRING ALL OF OUR KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCES TOGETHER.

TOGETHER WE KNOW MORE. TOGETHER WE ACHIEVE MORE. TOGETHER WE DO BETTER.

Published: March 7, 2023

Written by: Luz Mery Hernández P y Natalia Calderón – Salvaguarda Project

Salvaguarda (“Saveguard”) is an innovative project that aims to strengthen proactive environmental citizenship. The project is being implemented by HORIZONT3000 and Conciudadanía since 1.1.2020. It is funded by the European Union in the framework of its Civil Society Commitment and supported by the Austrian Development Agency (ADA), with funds of Austrian Development Cooperation, and the Dreikönigsaktion- Austria (DKA).

Since 1991, the Colombian organisation Conciudadanía has been fighting for the realisation of rights. Their work promotes citizen participation for the construction and democratic management of sustainable and peaceful territories through the exercise of full citizenship by men and women.

Although in Colombia there are no binding norms (laws, decrees) that oblige the establishment of an equal number of men and women in citizen participation bodies, the Salvaguarda project proposed to develop a series of provincial meetings with women from participating environmental organisations and collectives, in order to exchange experiences, reflect and learn about the role of women in environmental management and the parity of men and women in these participation bodies.

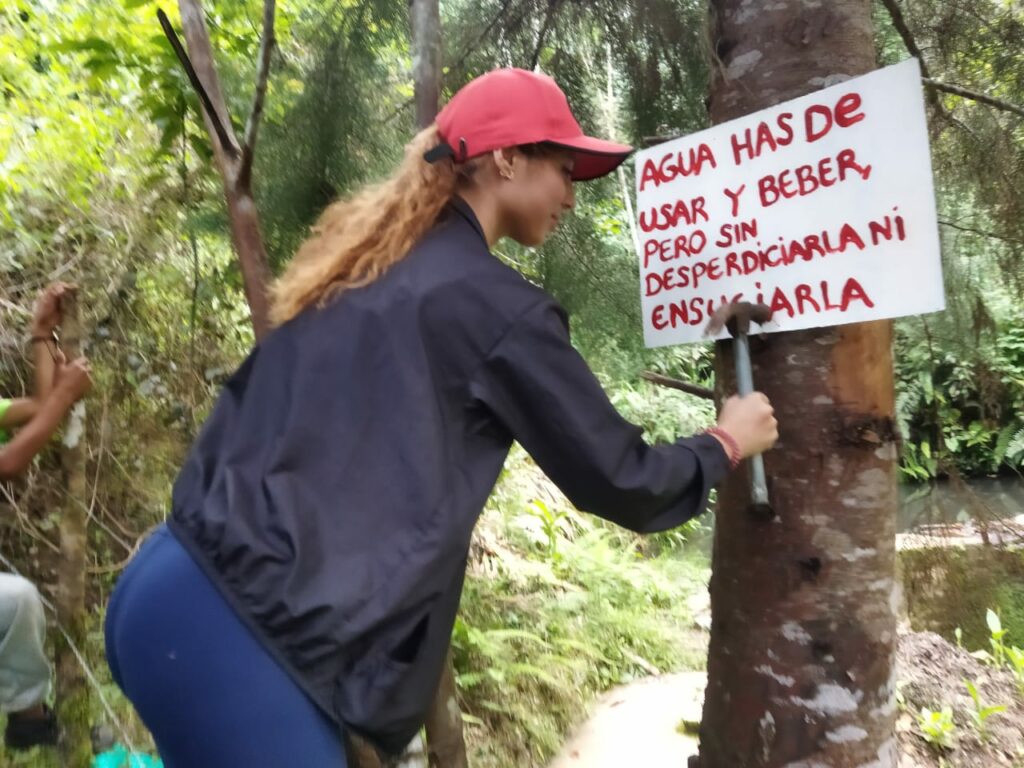

Salvaguarda has reflected on and understood the impact of women’s participation in environmental management – especially through various activities with women belonging to environmental roundtables, collectives, watershed councils, and boards of aqueducts in the east, southwest and west of Antioquia.

We began these reflections by mapping the body – corporal cartography – in a drawing made by these women themselves, which then became a map to identify their territory, related to their ailments, their dreams, their centres of connection with life.

We noticed, at first, the insistence in relation to repression towards women and anyone who defends territory in general terms: “It seems that defending what is ours does not please the rich and the governments. They prefer to give our land and our territories to companies whose only interest is to make money. Meanwhile, we, as women, put life at the centre”.

In these meetings, the women expressed a feeling of powerlessness and this was linked to the fear of making themselves visible. Gloria, from the municipality of San Jerónimo, stated that “we leaders are called to fight for the territory, but we cannot make ourselves visible because we will be the martyrs of tomorrow”.

Documentary short film about the work of Salvaguarda, 2021 (only in Spanish with automatic subtitles)

They also recognise the territory’s main conflicts, such as socio-environmental conflicts related to water (lack of a sense of belonging and taking care of water, water contamination with agrochemicals, water shortages, misuse of water sources, economic exploitation of water sources, poor quality in the provision of water services, privatisation of local aqueducts), deforestation, monocultures, lack of institutional commitment and lack of credibility in institutions, displacement due to power plants, the impact of mining on the social structure of the region and the mining companies’ threats against anyone defending the territory, and feminicides.

Marta Loaiza, inhabitant of the municipality of Titiribí, expressed, for example, that “when in times of flooding the media say that the river has deviated from its course, in reality the correct expression is that the river is returning to its course”.

Mabel Gómez, member of the Mesa Ambiental de Betania, said that “the water we drink in my municipality comes from its protected areas, so we have to take care of them like the apple of our eye, because water is as important for life as our own bloodstream”.

With regard to the role of women in citizen participation, the meetings made it possible to make visible women’s perception of the fact that their perseverance and work for the care of life has historically been disqualified and publicly unknown. Carlina Posada, from the municipality of Andes, summed it up when she stated that “women have not been recognised by politics“.

In order to highlight the notion of the empowerment of Salvaguarda women, the Salvaguarda Women’s Knowledge Exchanges were held. Women were invited to meet each other in a space of creation, self-affirmation and self-care.

In order to raise awareness of their inner potentials and the work they carry out as safeguards of life, different exercises and dances were performed to symbolise the human relationship with the elements that give life to life on the planet: air, water, earth, fire and sun.

The experience of the dance of life enabled the women to awaken to very meaningful, reflective and integrative understandings of their womanhood. This opened the door to listening to themselves, to self-love and peer support, which became evident in their reflections in the Diary of a Safeguarda.

Subsequently, work was carried out in subgroups for the exchange of knowledge and experiences in which they answered the questions: What knowledge do we have? From whom did they learn this knowledge? How can I share this knowledge with other women?

Phrases such as “Water reminds me that I am free” or “May my actions be as transparent as water” emerged in the read-alouds of the work with the Diary: “When I look at myself in the water, I see myself taking care of the environment, being an example of conservation, leaving my children a world in which they can breathe”. Genoveva Restrepo, from the municipality of Giraldo, expressed fear for what awaits her descendants if we continue to destroy the environment.

For her part, Adriana Londoño, Basin Councillor for the Sucio Alto river, sees in water the agricultural heritage that her parents left her: “I am worried about the countryside, we have to reactivate it, we have to work the land again, because if we do not take care of the countryside we will not have water or food”.

It is clear that at the heart of the essence of the Salvaguarda women is their love of the countryside, of working the land; they are the cradle of their dreams and concerns. For example, Luz Myriam Rodríguez, from Santa Fe de Antioquia, said: “I come from a very brave family, with hard-working hands, fighting women. Sharing and solidarity can be seen in the countryside”.

These meetings also made it possible to recognise the great potential of practical, professional and everyday knowledge and know-how that women have in environmental management within their territories. It can generate economies, fair markets, and more conscious processes between men and women aimed at restoring life in their communities by taking care of the planet and its natural resources.

In this respect, Viviana Urrea, a young woman from Cocorná, proudly stated: “I am a full-fledged farmer, there are few things I enjoy as much as planting and then being able to eat what I harvest”.

In the south-west of Antioquia, another woman said: “I live in the village of La Mercedes in Santa Bárbara. I am a health technician, I worked as a health promoter, and also as a catechist. I am a watershed advisor and I feel as a part of the territory. I have a plot of land where I grow organic coffee and trees for reforestation, I also have a community nursery. I recently sold 400 trees for the PORH of the Amaga River-Sinifaná stream”.

This exchanges between women also showed that in order to promote and sell products made in the municipalities, especially those made by women, a strategy is needed to qualify the quality and sale of products. There are many ideas, but limited marketing capacity. Concern was expressed about the difficulty of competing locally with the prices of large national companies such as D1.

According to one of the leaders of Western Antioquia, María Ruth Ospina, “we have lacked a lot of capacity for cooperation. Capitalism has put us in a place of competition and has made it difficult for us to be sororities”. As a result of the meeting of knowledge, some proposals emerged:

Then, in a third round of sub-regional women’s meetings, a question was asked: How does the woman safeguard, how does she care for herself and for the natural heritage? Here, it was surprising to find the variety of ways in which a woman cares for the natural heritage in her daily life.

For example, a teacher from the Southwest of Antioquia, says that in her career as an educator in the village, she set up a vegetable garden in the school because she realised that the children needed lunch, so “with the garden I could organise their lunch. I also taught the children about recycling and I give little bottles to the mothers so that they can sow at home and do not have to spend money in the village”.

Another woman said: “I am a great recycler of water and taking care of it is what I like the most, trying not to throw agrochemicals anywhere. I also promote ecological gardens in houses with plots of land. As a woman and an environmentalist, I fought and fought and said that they could not deforest these trees because they were the source of the spring near my house. We are six families collecting water from that spring and I am taking care of it, although further down they are throwing toilet paper in there”.

All the women, from different places and contexts, do some kind of sowing and planting, and they try to give new life to the water they collect.

A need to work on gender gaps was identified as a way of thinking about the disparity between men and women in terms of rights, resources and opportunities. This concept can be applied to different fields, such as work, politics, participation, education and the economy.

For this reason, during the last sub-regional meetings held in 2022, women reflected on the forms of subordination, oppression, discrimination and inequality that they experience in their environmental organisation and in the territories.

From these meetings, answers emerged that invite us to think about the structure that underlies the patriarchal system, which generates tacit relations of domination that are difficult to identify and also difficult to name.

Above all, it was identified how the culture has marked women very strongly in the sense that they have been conditioned to be the carers. Men tend to be excluded from the responsibilities of care in all its dimensions.

Regarding participation in public discussion, they say that men have a voice, while women, when they express their opinions, dissent or make proposals, are labelled as old witches, tiresome, “cantaletosas”, dramatic, exaggerated… among other adjectives.

In several cases, when the presidency of the collective, environmental board or watershed council is held by a man, they say that his voice is loud, he speaks harshly to express ideas, does not listen, does not supervise himself and believes that everything he does is “superb”.

Men in positions of power delegate women to workshops, learning spaces or where daily tasks are set, because they claim to be more productive and contemptuously tell them that “women have more time to go to meetings”. But they do go to decision-making spaces and to public speeches.

The need arose to review the ways of relating to other women, because in some cases, when they have roles of power in their organisations, they assume patriarchal and dominant ways of relating to other women.

The meetings also allowed us to visualise a recurring allusion in the three sub-regions to the obstacles that women face in citizen participation in general, given that they have various burdens in addition to work, and more conflicts related to economic situations and the responsibility of unpaid care in their homes.

Understanding the interrelationship between poverty, poor education and unemployment; violence against women and lack of autonomy; social, cultural and economic inequalities, and poor sexual and reproductive health, are factors that have serious implications for the achievement of women’s full citizenship.

This is why these interrelations were identified as one of the main aspects to be taken into account in understanding the gender gaps in environmental management.

It was gratifying to see how the women proposed to continue supporting the strengthening of the aqueducts in the villages, because they are certain that healthy water is good for them and the community in general. It reduces the time spent on household activities (such as boiling water for cooking or drinking, or having to wash by hand because the washing machine gets clogged with muddy water from badly maintained aqueducts).

This example shows that there is a need to strengthen environmental initiatives led by women with economic resources and public visibility, as well as the need to support productive entrepreneurship, which in addition to caring for the natural heritage, ensures their economic autonomy in order to escape from cycles of gender-based violence.

The Salvaguarda project has contributed in a concrete way in financing sub-regional and local meetings, in generating mixed discussion between men and women in departmental meetings and in the aqueduct boards, and promoting space for reflection, for emotional support with the accompaniment of experts, and for the sharing of seeds, plants, and knowledge in the care of the natural heritage.

Sources: