Make Your Experiences Count. They Can Change the World.

LET’S BRING ALL OF OUR KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCES TOGETHER.

TOGETHER WE KNOW MORE. TOGETHER WE ACHIEVE MORE. TOGETHER WE DO BETTER.

LET’S BRING ALL OF OUR KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERIENCES TOGETHER.

TOGETHER WE KNOW MORE. TOGETHER WE ACHIEVE MORE. TOGETHER WE DO BETTER.

Published: August 22, 2022

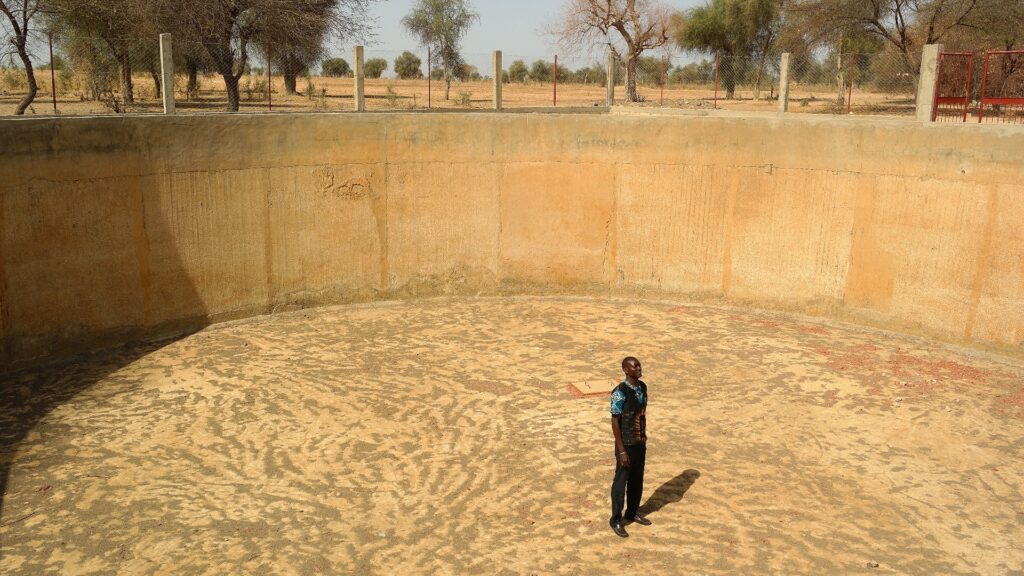

How can you get easy access to safe drinking water when boreholes are contaminated with too much fluoride and mineral salt? For many years, this was a pressing question for communities in the Fatick region, located in the Sahel Zone of Western Senegal. A solution was found in the form of so-called Rainwater Harvesting systems (RWH). One big advantage of this system compared to boreholes is that you don’t depend on ground water quality. Instead, you rely on collecting rainwater and using simple filter systems to get purified and healthy water.

Funded by LED (Liechtensteinischer Entwicklungsdienst) and WHG (Welthaus Graz) and under the guidance of the diocese Caritas-Kaolack and HORIZONT3000, a four-year-long project started in 2017 to implement Rainwater Harvesting systems in ten villages across the region. The project was divided into two phases: The first concerned the building of tanks, basins, and accompanying filters itself. It also included the setting up of “school gardens” in order to use the clean water for ecological agriculture. A sustainable rainwater management should not only contribute to pupil’s health but also transform often baren school grounds into pedagogical sites which provide healthy food and shade.

The second phase focused not so much on building infrastructure but on training and awareness-raising work. The goal of this consolidation phase was the complete takeover of all activities by the communities themselves, especially the management committees set up within the ten villages. After all, a sustainable management of rainwater is a collective concern of all residents.

In 2022 this project has now reached its end. Time for us to take a look back. We talked with Senegalese technician Boucar Diouf about his feelings on this long-time project, its lasting impacts and future prospects.

What was your role in the project?

I was in charge of setting up a technical planning and monitoring the execution of the activities as well as the budget limitations. I also made technical reports and evaluated the project.

What were the reactions at the end of the project?

Although the second phase of the project was implemented in a very difficult context regarding the Covid-19 situation, it was a success. The communities in general now recognise the importance of rainwater harvesting systems and all the benefits they come along with. Of course, there is a little bit of uncertainty now that the project has ended. Everybody here would like to extend this experience with rainwater harvesting. It has certainly established itself as a good alternative to other sources of water in this zone.

Did you experience a particularly heart-warming or perhaps frustrating moment during the project that you would like to share with us?

I did note two very contrasting moments in relation to the involvement of the beneficiaries. The first one was a rather unexpected initiative by the village of Boustane Diaw. During the intense period of the covid pandemic, when visits there were nearly impossible, they renewed the drainage system without our intervention. So they themselves identified the necessary repairs and took the matter in their own hands!

In contrast, the other moment was quite sad. During a visit to Soumbel Keur Latyr we found a tank emptied of water because the pump had been operated by an unknown person. Well, you simply cannot have control over everything all the time, for better or for worse. What these moments demonstrate, is that the sustainability and autonomous management of Rainwater Harvesting systems depend on good community organizational dynamics.

What impacts have been noted outside of water and health benefits? Have you noticed any ecological awareness or strengthening of solidarity and organizational capacity?

The schools, for one, were an area where the Rainwater Harvesting systems were connected to a whole range of activities. With the availability of good water, organic school gardens were made possible. Pupils can now grow their own vegetables, fruit trees, and herbs within the school grounds and contribute to a sustainable management of the environment. But not only pupils are involved here. The whole community participates in this ecological farming, strengthening the communities’ awareness of the harms of conventional agriculture. One thing is sure: these school gardens as a pedagogical support at school level is an approach that needs to be disseminated on a larger scale!

Over the past years, did you ever think that the project would fail?

No, I always thought the project would succeed, especially after Phase 1, when we turned to the continuation and consolidation of the achievements made.

What are the prospects after this project? Will there be another phase financed by other donors? What is the next step for Caritas in this area?

There is definitively a need for another project phase with larger intervention sites. This is why we are already elaborating a new request for the extension of the project. It should not only deal with Rainwater Harvesting itself but also integrate other aspects connected to it more strongly, like food security and rural entrepreneurship.

In this regard, the Caritas management has tried to contact the FAO project which is being implemented in this area, but there is no positive response yet. Caritas Kaolack is meanwhile still working in the area as part of another project to strengthen food security, with a focus on agro-ecology. In any case, we remain confident. As for now, some local authorities have already committed themselves to support the financing of Rainwater Harvesting systems in their search for partners.